Inheritance

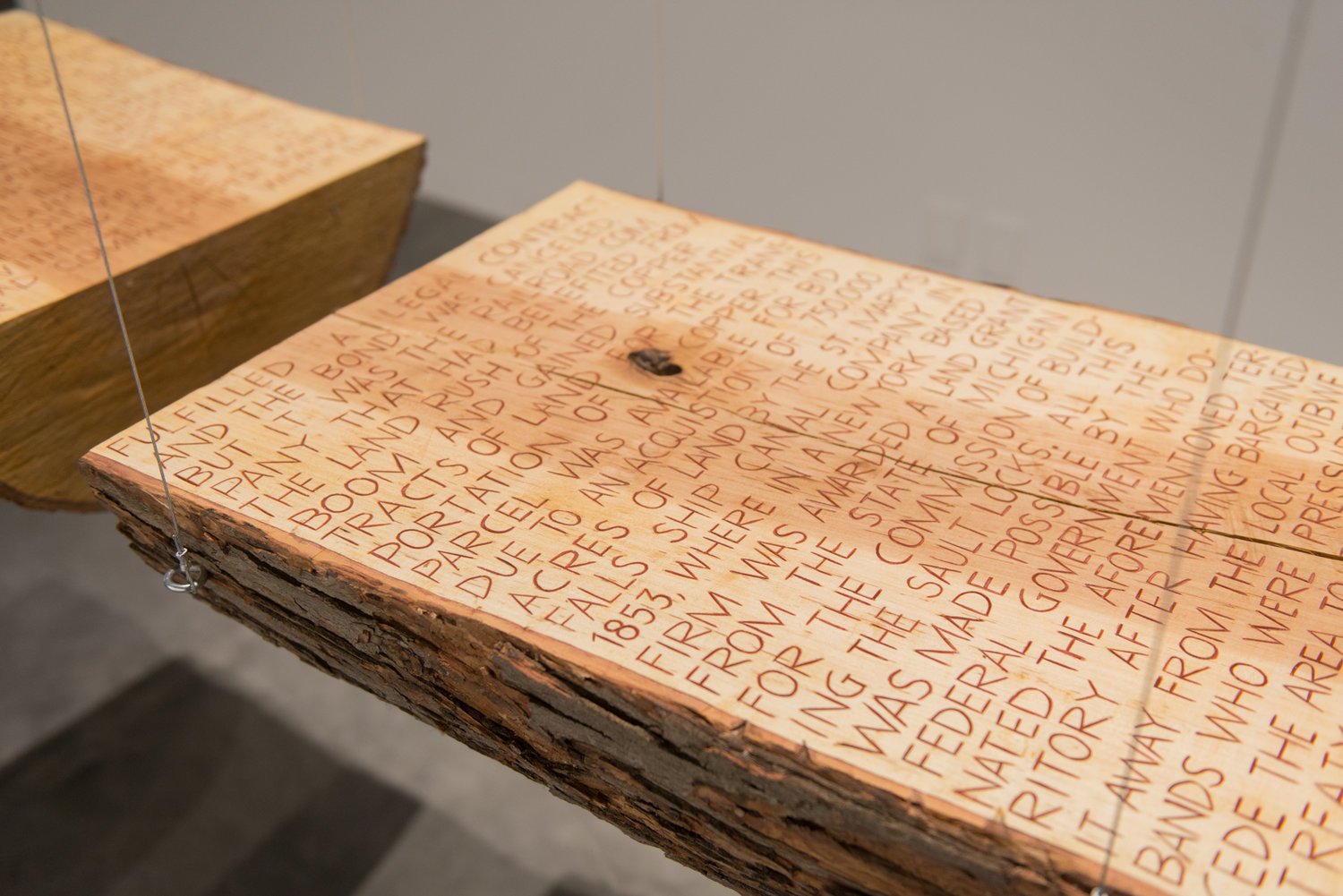

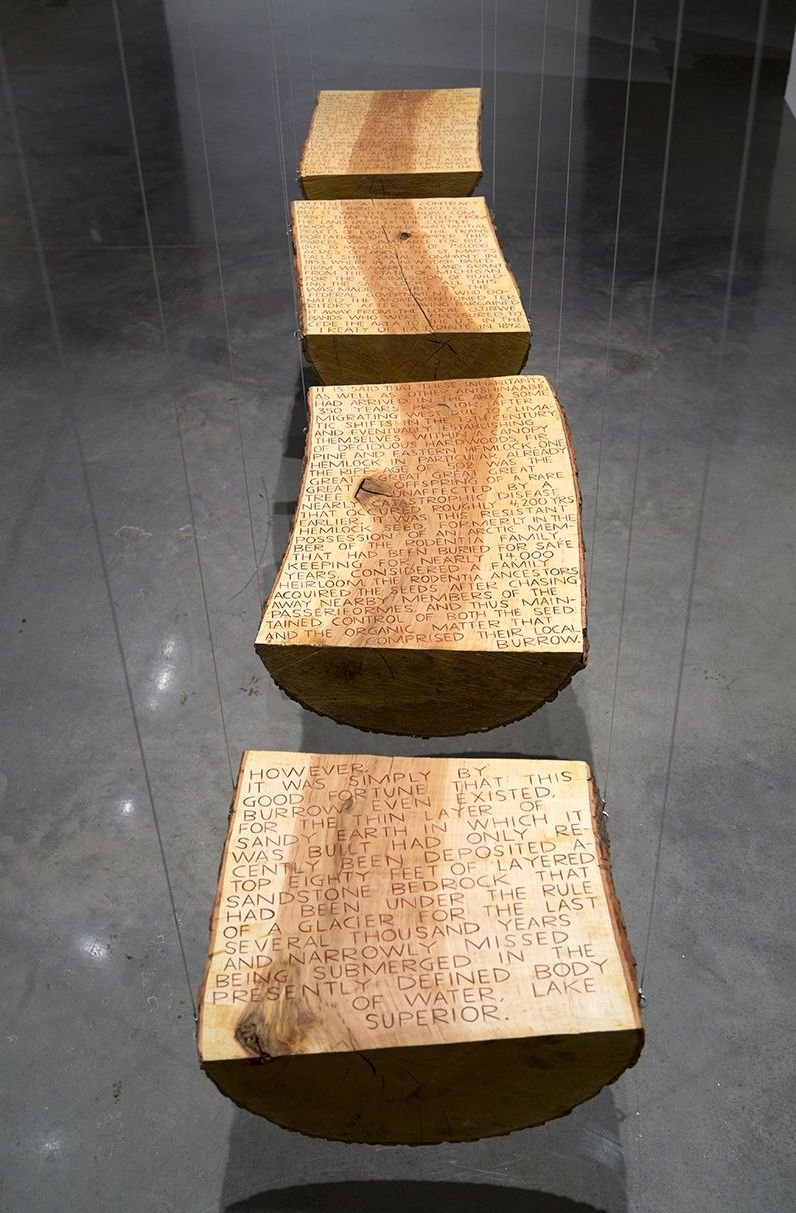

Largely influenced by my childhood in the rural Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Inheritance, is a way I interrogate my relationship to a particular piece of forestland that harbors the house I grew up in, and the twenty acres that may or may not come into my name in the future. I ask myself who owns the forest? and I trace the product of paper to its origins, reflecting on the colonial roots nature of property and ownership. Floating a waist height, the fragmented trunk alludes to the relic of this continuing history.

The first paragraph is printed on a piece of paper which I traced from a local warehouse for this project. The rest is hand-carved into silver maple.

“Upon printing this piece of paper I could declare not only the ownership to the words printed in ink, but the fibers of cellulose, pressed and processed, of which I exchanged of my thirteen dollars and ninety-eight cents for just several days prior. Moments before that exchange, this sheet, along with 249 others, were briefly in the possession of local paper store in Plymouth, MN who had sourced the coated paper line from a national corporation who had recently purchased several long standing locally owned paper and pulp mills in Michigan.

(now continues the text carved into the log segments)

Under new ownership, several mills continued to purchase pulp timber from the nine of the top landholders of over 2 million acres of commercial forestland across Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. One landowner in particular, The Heartwood Forest Fund II, hired a local sawyer in back in 2012 to log a 260-acre parcel outside of Edgmere Junction, which had changed hands in the timber industry for decades dating back to 1942. It was this parcel that was first leased to Blazer Brothers, of Blazer’s Mill. The two brothers, who were Dutch wrestlers from Detroit, had briefly rented the forestland from the Copper Range Railroad Company, however, having never fulfilled the terms of their agreement the bond was cancelled after a year. Nonetheless, it was the railroad company who benefited from the land rush of the copper boom having gained substantial tracts of land for the transportation of copper. The aforementioned parcel was available to the railroad for bid due to an acquisition of 750,000 acres of land by St Mary’s Falls Ship Canal Company in 1853, where in a New York based firm was awarded a land grant from the State of Michigan for the commission of building the Sault Locks. All this was made possible by the federal government, who donated the territory after having bargained it away from the local Ojibwe bands, who were pressured to cede the land to the US in the Treaty of La Pointe in 1842.

It is said that these inhabitants as well as other Anishinaabe, had arrived in the area roughly 350 years prior, after migrating west due to climatic shifts in the 15th century and eventually establishing themselves within a canopy of deciduous hardwoods, fir, pine and eastern hemlock. One Hemlock in particular, already the ripe age of 502, was the great great great great great offspring of a rare tree unaffected by a nearly catastrophic disease that occurred roughly 4,200 years prior. It was this unaffected hemlock seed, which had been in possession of an arctic member of the Rodentia family, that had been buried it for safe keeping for nearly 14,000 years. Considered a family heirloom, those Rodentia acquired the seeds after chasing away nearby members of the Passeriformes, and thus controlled both the seed and the organic matter that comprised their local burrow. It was only luck that allowed this win, for the soil was only recently deposited atop 80 feet of sandstone that had been under the rule of a glacier for several thousand years, and narrowly missed being submerged in the presently defined body of water, Lake Superior.”